Library Hours:

- Mon – Wed:9 AM – 9 PM

- Thur – Fri:9 AM – 7 PM

- Sat:9 AM – 4 PM

- Sun:Closed

Native American Settlement of the Franklin Park Area

The Potawatomi (“People of the Place of Fire”) are a tribe of the Algonquin language family, closely related to the Ottawa (“To Buy and Sell”) & Ojibwa (“To Roast Till Puckered Up”). The three Indian nations inhabited the Great Lakes region. The predominant tribe were the Potawatomi. Initial French records suggest the Potawtomi occupied the southwest quadrant of the lower peninsula of Michigan, prior to 1640. They moved southward. By the beginning of the 17th century they had established themselves at the Milwaukee River (Milwaukee, Wisc.) and the St. Joseph River (St. Joseph, Mich.). By the close of the 17th century, the Potawatomi occupied the area around the southern portion of Lake Michigan, extending southwest over a large part of Illinois east across Michigan to Lake Erie and south to Indiana. Within this territory they had about 100 villages. The Potawatomi moved into the Chicago region in about 1743.

During the French & Indian Wars (1756-1763), the Potawatomi sided with the French. In the beginning of the American Revolution, in 1775, they took up arms against the U.S. and continued hostilities until the Treaty of Greenville, in 1795. (Indians residing in Ohio agreed to stay north and west of a line running east from the Indiana border almost half of the way south through Ohio and about three-quarters of the distance from Indiana to Pennsylvania.The white man was to stay south and east of the line) The Potawatomi alsotook up arms against the U.S., siding with the British in 1812. They made final treaties of peace in 1815. Removal of the Indians took place on September 28, 1835. In 1838 more Indians were removed. As of 1839, Potawatomi still remained.

The Potawatomi were organized into 30 or more clans with each man inheriting the clan of his father. Villages were ruled by a chief who was responsible to a council of elders. Religious leaders included 3 classes of Shaman: Doctors, Diviners & Advisor Magicians. (Shaman were Medicine Men or Spiritual Leaders of the Tribe). Religion was intensely personal, with vision seeking through fasting. The Potawatomi had many festivals and ceremonies, such as the Medicine Dance, War Dance & Sacred Bundle Ceremony. Sacred bundles were a powerful part of ceremonies especially linked to planting and harvesting. They were made from bison hide and contained tools necessary for rituals and ceremonies. They were passed from generation to generation. Women owned the Sacred Bundle but they could only be used by men.

Potawatomi believed in an afterlife somewhere in the West. Burial customs varied with time and place. In early times they practiced cremation, while others employed scaffold burials. Scaffold burials employed the use of a scaffold upon which the body of the deceased was hoisted. Food, drink and personal possessions were laid next to the body. The body was left from 4-6 months. When the body began to decompose, a bone-picker (undertaker – who grew his fingernails very long) ascended the platform, to pick the rotted flesh off the body. When this was completed the bones were given to the family and the remaining flesh was burned. In later times, people were buried amid personal items they might need in their journey. A shelter was built over the grave. The family might ceremonially adopt a person to take the place of the deceased.

Villages were usually built along streams and composed of large bark-covered lodges or small mat-covered dome shaped wigwams, both constructed over a pole framework. The Potawatomi had a diversified economy. They raised corn, beans, peas, squash, melons and tobacco. They sold surplus to the traders. After the harvest they began the winter hunt, which lasted several months. Deer, elk, bear, beaver and fish abounded. Maple sap was gathered in the spring and boiled into syrup and sugar. Beechnuts were gathered in autumn and pounded into flour. Women made pottery and men made fine birchbark canoes. Clothing was made of skins and furs decorated with paint and quillwork. Men practiced tattooing and both men and women used body paint.

Josette (LaFramboise) Beaubien

In 1804, John Kinzie and his family, along with their housekeeper a half- Indian, half-white woman named Josette LaFramboise, traveled to Chicago to

begin what became a very successful 8-year, fur trade business. They were the first citizens of Chicago. Josette was the sister of Claude LaFramboise. She was born in 1796. In 1812, she became 16 years old and married Jean Baptiste Beaubien. In 1833, Josette (LaFramboise) Beaubien and her husband (Jean Baptiste Beaubien) purchased the northern half of Claude LaFramboise’s reserve. Josette Beaubien died at the age of 49, in 1845. As she had lived her last years in what was to become the Franklin Park area, she was buried in the vicinity of River Road north of King Street. A tombstone has been placed there in her memory. Jesse Walker purchased the southern half of the reserve. As a side note, William Draper was the first White man to settle in what was to become Franklin Park. In 1837, he purchased land near the Des Plaines River.

begin what became a very successful 8-year, fur trade business. They were the first citizens of Chicago. Josette was the sister of Claude LaFramboise. She was born in 1796. In 1812, she became 16 years old and married Jean Baptiste Beaubien. In 1833, Josette (LaFramboise) Beaubien and her husband (Jean Baptiste Beaubien) purchased the northern half of Claude LaFramboise’s reserve. Josette Beaubien died at the age of 49, in 1845. As she had lived her last years in what was to become the Franklin Park area, she was buried in the vicinity of River Road north of King Street. A tombstone has been placed there in her memory. Jesse Walker purchased the southern half of the reserve. As a side note, William Draper was the first White man to settle in what was to become Franklin Park. In 1837, he purchased land near the Des Plaines River.

![native reserves map]() Claude LaFrambois

Claude LaFrambois

Claude LaFrambois (French: “the raspberry”) was born in 1809 of a Potawatomi Princess and a French/ Canadian trapper, in Upper Michigan. He was one of the signers of a petition to the Catholic Bishop of St. Louis to have a priest sent to Chicago. Claude LaFramboise was recorded as a??? the Des Plaines River for his help with the Blackhawk War, in 1832. The section of land ran from Addison St. (on the north) to Grand Ave. (on the south) and Indian Boundary Line (on the east) to Pueblo Ave. (on the southeast). This triangular shaped tract was 640 acres. When the Indians left Illinois, for Council Bluffs, Iowa, he went along as an interpreter and later returned to Chicago. In 1840, Claude LaFramboise moved to an area along the Des Plaines River. It is suggested that at the time of LaFramboise’s death he was buried south of Grand Ave. along the Soo Railroad tracks. A cement marker had marked the burial place.

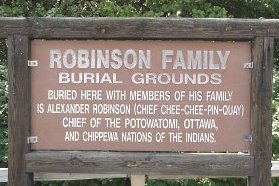

Alexander Robinson

Alexander Robinson (Che Che Pin Qua – “Winking Eye”) was reportedly born in 1762, in Mackinac, Michigan. He died in 1872 in the area, which was near what was to become Franklin Park. His father was a Scotch Trader, who had been an officer in the British Army and his mother was of French/Indian (Ottawa) heritage. He was Chief of the United Potawatomi, Chippewa (Ojibwa) and Ottawa Indians. He moved to St. Joseph (not the St. Joseph we know today, as this St. Joseph was near Niles, Michigan) where he became a trader. He probably visited what was to become Chicago as early as 1806 and acted as a guide for the first permanent Indian agent in the area in 1807. In 1814, he put down his roots and settled permanently in Chicago. He, with his partner (Antoine Ouilmette, for whom the city of Wilmette is named), cultivated the land belonging to Ft. Dearborn, raising corn until Captain Bradley arrived to rebuild the fort in 1816. He served as a government interpreter from 1823-1826. He was a recorded voter in 1825, 1826 and 1830. In 1830, he was licensed to open a tavern in Chicago. Prior to this, he had owned a cabin or trading post at Hardscrabble (the Bridgeport section of Chicago) but vacated it before 1826.

John Kinzie married Alexander Robinson to Catherine Chevalier, daughter of Francois Chevalier, who was half-Indian and half-French. Francois was Chief of the United Potawatomi, Ottawa and Chippewa (Ojibwa) Indians. After Francois’ death, Alexander was named Chief of the three tribes. With the signing of the Treaty of Prairie du Chein, in 1829, he was awarded land, as Claude LaFramboise was, by the Federal government for his help in the Blackhawk War. He was also awarded additional land for his aid to the white man, in general, and for his help in rescuing people during the Fort Dearborn Massacre. He arrived too late to prevent the massacre, however he was able to safely transport many people, including John Kinzie (and his family) and Captain Helm (and his wife) across Lake Michigan by canoe.

John Kinzie married Alexander Robinson to Catherine Chevalier, daughter of Francois Chevalier, who was half-Indian and half-French. Francois was Chief of the United Potawatomi, Ottawa and Chippewa (Ojibwa) Indians. After Francois’ death, Alexander was named Chief of the three tribes. With the signing of the Treaty of Prairie du Chein, in 1829, he was awarded land, as Claude LaFramboise was, by the Federal government for his help in the Blackhawk War. He was also awarded additional land for his aid to the white man, in general, and for his help in rescuing people during the Fort Dearborn Massacre. He arrived too late to prevent the massacre, however he was able to safely transport many people, including John Kinzie (and his family) and Captain Helm (and his wife) across Lake Michigan by canoe.

Alexander Robinson was a key figure in the effort to bring a religious leader to Chicago, as there were no clergy at this time. Due to his efforts, in large part, the Catholic Bishop in St. Louis sent a priest (Father John St. Cyr) to Chicago. His land lay directly north of Claude LaFramboise’s reserve. It reached Foster Ave. (on the north), Addison St. (on the south), the Des Plaines River (on the east) and Rose St. (25th Ave., on the west). He lived on the reserve from 1836 until his death on April 22, 1872. A family plot is located along East River Road near Lawrence Ave., where his remains and those of his family are located. A tombstone marks the site.

Alexander Robinson was a key figure in the effort to bring a religious leader to Chicago, as there were no clergy at this time. Due to his efforts, in large part, the Catholic Bishop in St. Louis sent a priest (Father John St. Cyr) to Chicago. His land lay directly north of Claude LaFramboise’s reserve. It reached Foster Ave. (on the north), Addison St. (on the south), the Des Plaines River (on the east) and Rose St. (25th Ave., on the west). He lived on the reserve from 1836 until his death on April 22, 1872. A family plot is located along East River Road near Lawrence Ave., where his remains and those of his family are located. A tombstone marks the site. A family home, built by Indians using wooden pegs, stood just west of the burial ground. It burned down on May 25, 1955. Alexander Robinson was reported to have been a teetotaler. He was asked to speak at a temperance meeting in Chicago. At that meeting he removed an empty bottle of whiskey from his waistcoat and smashed it with a tomahawk, to prove that he had given up liquor and that he believed it was bad for people. Another interesting note about Alexander Robinson, was that at the signing of the treaty to move the three tribes west, he signed with an “X”, even though he was a literate man. Why he did this, we can only guess. We believe that Franklin Park’s 2nd mayor, Charles B. Robinson, might have been related to Alexander Robinson. Charles B. Robinson’s son had a lazy eye just as Alexander Robinson did, and the resemblance between Alexander Robinson and Charles B. Robinson’s son is remarkable.

A family home, built by Indians using wooden pegs, stood just west of the burial ground. It burned down on May 25, 1955. Alexander Robinson was reported to have been a teetotaler. He was asked to speak at a temperance meeting in Chicago. At that meeting he removed an empty bottle of whiskey from his waistcoat and smashed it with a tomahawk, to prove that he had given up liquor and that he believed it was bad for people. Another interesting note about Alexander Robinson, was that at the signing of the treaty to move the three tribes west, he signed with an “X”, even though he was a literate man. Why he did this, we can only guess. We believe that Franklin Park’s 2nd mayor, Charles B. Robinson, might have been related to Alexander Robinson. Charles B. Robinson’s son had a lazy eye just as Alexander Robinson did, and the resemblance between Alexander Robinson and Charles B. Robinson’s son is remarkable.

Claude LaFrambois

Claude LaFrambois